This article provides an analysis of the new provisions in the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) that govern Mutual Legal Assistance in criminal matters. While only few provisions of the European Investigation Order are picked up by the TCA, it is mostly based on the Council of Europe’s European Mutual Assistance Convention of 1959. An overview of the applicable law is provided, after which a closer look is taken at procedural aspects in general as well as specific differences between previously applicable and new provisions. In this respect, two conditions for issuing a request are considered, namely availability in similar domestic cases and proportionality. Grounds for refusal, provisional measures and legal remedies also are highlighted. The authors conclude that the new provisions leave a lot of unanswered questions and that while mutual legal assistance can continue, it will happen at reduced pace.

Authored by Ben Keith, Barrister, 5SAH Chambers, London, UK and Anna Oehmichen at

Knierim & Kollegen, Mainz, Germany for NJECL: examining Mutual legal assistance (MLA) under the EU–UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement.1

Introduction

On 24 December 2020, the European Union and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and

Northern Ireland reached an agreement in principle on the EU–UK Trade and Cooperation

Agreement (TCA).

As the procedure of Art 218 Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU)2 needed to

be observed, it was not possible to reach a final agreement by 1 January 2021. Therefore, it was

decided to apply the TCA on a provisional basis as of 1 January 2021, for a limited period of time

until 28 February 2021.3

Albeit provisional, the TCA will be directly applicable in all Member States pursuant to Art

216(2) TFEU.

The Council, acting by the unanimity of all 27 Member States, on 29 December 2020,

adopted, by written procedure, a decision authorising the signature of the Agreement and its

provisional application as of 1 January 2021.4 On the UK side, the Government published the

European Union (Future Relationship) Bill5 on 29 December. Parliament was recalled on 30

December to approve the legislation. The Bill was rushed through Parliament at incredible

speed: it was scheduled to go through all of its Commons and Lords stages before 31 December

so that, if passed, it could receive Royal Assent before the end of the transition period.6 And,

indeed, on 31 December 2020, the European Union (Future Relationship) Act 2020 was

passed.7

The European Parliament has been asked to give its consent to the TCA.

As a last step, the Council must adopt the decision on the conclusion of the TCA. In the

meantime, Member States are requested to speedily submit relevant notifications to the Agreement. In the following, we shall analyse the new provisions that govern Mutual Legal Assistance (MLA) in criminal matters as of 1 January 2021.8

Overview

MLA is dealt with in Title VIII of the TCA. In general, it will now be based on the Council of

Europe’s (CoE) European Mutual Assistance Convention of 1959 (1959 CoE MLA Convention

or ‘Mother Convention’) and its additional protocols,9 as it was prior to the UK adopting the

European Investigation Order (EIO). However, the TCA also picks up some of the provisions of

the EIO, such as, for example, the principle of proportionality10 and the possible recourse to an alternative investigative measure if the requested measure does not exist in the executing

state.11 To take into account the change from mutual recognition to classical mutual legal assistance, the terminology has changed from “issuing” and “executing” authority back to “requested State” and “requesting State”.

Applicable law

When it comes to exchanging information on previous convictions, Title IX12 shall take precedence.13 Moreover, with regards to the freezing and confiscation, MLA will be governed by the more specific Title XI.14 With regards to combatting VAT fraud, a different Chapter regulates this area of law, and provides for some specifics regarding MLA in this area of law.15

For all other forms of MLA, the 1959 CoE MLA Convention with its Additional Protocols shall

be (or remain) the applicable law.16 In addition, MLA is also regulated in crime-specific

Conventions.17

Additional provisions of this Title are only aimed at ‘supplementing’ the existing regulations.

However, where the provisions in the Agreement are more specific, they will supersede the

provisions of the CoE MLA system, and, where there are contradictions, the provisions of the

Agreement will prevail over those of the CoE MLA system (lex posterior derogat lex priori).

In this context, CoE conventions need to be accessed and analysed carefully, including their

signatures and ratifications, declarations, reservations, translations into selected languages and their explanatory reports. Unlike the EU, the CoE provides a Treaty Office updating the entire CoE status which is easy to access and updated daily.18

Procedural Aspects

Unlike the new arrest warrant procedure and the new regulations on freezing and confiscation, for which the Agreement already foresees a form19, in the case of MLA, the Specialised Committee on Law Enforcement and Judicial Cooperation20 is tasked to establish a standard form for requests. Since the parties agreed to go back to the classic CoE MLA system, picking up only some elements of the EIO, a lot of modifications to the EIO form would have been required in very short time.

It is likely that the standard form will follow the example of the EIO, with all the limitations

arising from the new regime. Until this form will be established, requests will be made in the

classical way of judicial cooperation and specific diplomatic and police channels, that is, letters

rogatory.21

The competent authorities are those that are competent under the CoE MLA system and as

defined by States in their respective declarations addressed to the Secretary-General of the Council of Europe.

In the UK, this is the UK Central Authority.22 In all other Member States, the authorities

will generally be again those competent under the CoE MLA system. Art. 4 of the Second

Additional Protocol to the 1959 CoE MLA Convention23 provides a differentiated system of

channels of communication, depending on the type of the requested assistance. The

Agreement specifies that in those cases where direct transmission is provided for under the

respective provisions, requests for mutual assistance may also be transmitted directly by

public prosecutors in the United Kingdom to competent authorities of the Member States. This

means that in the UK, prosecutors will now be directly competent for the following types of

request:24

- Proceedings brought by the administrative authorities

- Controlled delivery and covert investigation

- Temporary transfer of detained persons

- Copies of convictions.

It is likely that some Member States will make a similar declaration to the 1959 CoE MLA

Convention to allow for direct transmission through their public prosecutors as well. In urgent cases, any request for assistance or spontaneous information may also be transmitted through Interpol25 or via Europol or Eurojust.26

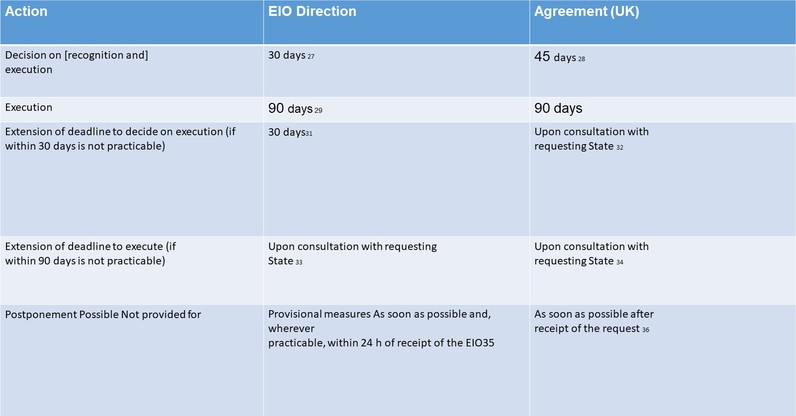

As Art 1 of the EIO Directive no longer applies, the request can no longer be made by a suspected or accused person, or by a lawyer on his behalf, but only by the respective competent authority. Time limits have been amended in the Agreement as follows:

Certain petty offences or, depending on the jurisdiction, regulatory violations, such as failure to

wear a seat belt, are exempted from these time limits.37 It is surprising that such examples are

listed at all as they will not meet the proportionality threshold provided for in the Agreement.38 In

any event, the list can never be seen as exhaustive, as all other petty offences would also not meet the proportionality threshold. Proportionality will always depend on the specific measure requested via MLA. However, if a coercive measure is concerned, which has significant impact on

fundamental rights (e.g., house search or wiretapping), the threshold established for proportionality by the issuing of EAWs or now ‘arrest warrants’ (EU–UK arrest warrants) based on

this Agreement can help as guidance, as well as the UK case law on the application of s.21A of the UK Extradition Act 2003.39

Conditions for issuing a request

As for the EIO, the Agreement provides for two conditions for a request for mutual assistance.40

These conditions are that:

1. the request must be necessary and proportionate for the purpose of the proceedings, and

2. the requested measure would have also been available under the same conditions in a similar

domestic case (i.e., of the requested State).

If these conditions are not met, the requested State may consult the requesting State and the

requesting State may withdraw or amend its request.

In addition, the obligation to inform about the execution of the EIO as provided for in Art 16 of

the EIO Directive has been replaced by a mere obligation to inform about the impossibility to

execute an MLA request or the appropriateness to carry out investigative measures not initially

foreseen, in order to enable the competent authority of the requesting State to take further action in the specific case.41

Non-availability in similar domestic cases

In case the measure requested is not available under the same conditions in the requested State,

before denying the request, the requested State shall consider recourse to an alternative measure.42

However, as in the EIO Directive, the measures listed exhaustively in Art LAW.MUTAS.117

(2)(a)–(d) of the Agreement are deemed to be always available so that for these measures no

alternative investigative measure can be used. The list is similar to the one in Art 10 of EIO

Directive, however, with one important difference: information or evidence which is already in the

possession of the executing authority is no longer available on a mandatory basis. So, even if in the context of domestic criminal proceedings regarding other, more serious offences, the executing authority has already obtained telecommunication data of a suspect that may also be requested by another State, this information does not have to be provided if for the offence for which it is being requested it could not be obtained under the law of the requesting State. However, the practical relevance of this difference will be limited, given that the evidence still must be available if it is contained in a database of the police or judicial authorities.43

In a case where the requested investigative measure is not available under the law of the requested State, the requested State will not be able to provide assistance and has to inform the

requesting State accordingly.44

Proportionality

Before denying the request, the requested State may consider whether it may use an alternative

investigative measure that would achieve the same result by less intrusive means than the investigative measure indicated in the request.

However, if such alternative measures are not available, it is unclear what consequences this will

have. Given the prominence proportionality plays in the Agreement,45 it is likely that a disproportionate request will be dismissed by the UK. (At least) by means of reciprocity, it must be expected that EU Member States will also declare disproportionate requests as inadmissible. In such cases, they are obliged to inform the requesting State ‘by any means and without undue delay’.46

The fact that proportionality is now expressly stipulated as a general requirement of MLA in the

Agreement means it will now apply to all sorts of MLA between the UK and EU Member States

(e.g., to service of documents) and is no longer limited to requests governed by the EIO.

Grounds for refusal

The exhaustive list of Art 11 of the EIO Directive no longer applies. Instead, the CoE MLA system

applies again. Art. 2 of the 1959 CoE MLA Convention provides two optional grounds for refusal,

namely, the political and fiscal offence exception (if the request concerns an offence which the

requested Party considers a political offence, an offence connected with a political offence or a fiscal offence), and the domestic order public, that is, if the requested Party considers that execution of the request is likely to prejudice the sovereignty, security, order public or other essential interests of its country.47

In this context, Art 6 of the Treaty on European Union48 should not be underestimated: the

ground for refusal based on human rights violations will still be de facto applicable. As the TCA49

clarifies that the cooperation in this Part is based on the Parties’ and Member States’ ‘long-standing respect for democracy, the rule of law and the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms of individuals, including as set out in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and in the European Convention on Human Rights, and on the importance of giving effect to the rights and freedoms in that Convention domestically,’ cooperation shall also be based (and depend) on observing the human rights the respective Party is bound by. This is not limited to the rights guaranteed by the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)50, but also includes human rights enshrined in other international human rights instruments such as the International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights of 19 December 1966 (ICCPR).51

For the transfer of detained persons, special optional grounds for refusal are contained in Art 3 of

the Second Additional Protocol to the 1959 CoE MLA Convention.52 Additional grounds for refusal (mandatory and optional ones) may be contained in the Additional Protocols to the Mother

Convention, in bilateral supplemental agreements, or in other crime-specific Conventions,53 always keeping in mind relevant Reservations or Declarations of the concerned Member State(s).

These grounds for refusal are now supplemented in the Agreement by another important, but

only optional ground for refusal provided for in the Agreement:54 ne bis in idem.

Provisional measures

Provisional measures (e.g., freezing of data to preserve evidence) as provided for in the CoE MLA system55 can only be lifted after the requesting State has been given the opportunity to present its reasons in favour of continuing the measure. This idea has been adopted from the EIO Directive,56 but can also be found in other MLA instruments.57

Legal Remedies

One achievement of the EIO Directive was that it obliged Member States to provide for legal

remedies against EIOs equivalent to those available at the domestic level. This provision has not

been incorporated into the Agreement so that the availability of legal remedies against requests will now again depends largely on the legal situation of each Member State. However, the right to

remedy is also enshrined in the fair trial principle of Art 6 of the ECHR and Art. 14(5) ICCPR for

convictions and sentences.58 As the TCA59 at least clarifies that the cooperation in this Part is based on the Parties’ and Member States’ long-standing respect for democracy, the rule of law and the protection of fundamental rights and freedoms of individuals, including the ECHR, cooperation shall also be based (and depend) on observing the human right to a legal remedy.

Scope of Application

Temporal Application

Art 62 of the Withdrawal Agreement60 provided for transitionary regulations for pending cases:

1. In the United Kingdom, as well as in the Member States in situations involving the United Kingdom, the following acts shall apply as follows: (…)

(a) the Convention, established by the Council in accordance with Article 34 of the Treaty on European Union on Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters between the Member States of the European Union (46), and the Protocol established by the Council in accordance with Article 34 of the Treaty on European Union to the Convention on Mutual Assistance in Criminal Matters between the Member States of the European Union (47), shall apply in respect of mutual legal assistance requests received under the respective instrument before the end of the transition period by the central authority or judicial authority; (…)

(l) Directive 2014/41/EU (…) shall apply in respect of European Investigation Orders received before the end of the transition period (…).

This is implemented by Art 185 of the same agreement commencing at the end of the transition

period.61 It is therefore the case that old EIOs will be treated as being under the EIO scheme,

however, without recourse to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). It will be interesting to see how this develops.

Requests incoming after 31 December 2020 will follow the provisions of the Agreement.

Territorial Application

The territorial scope is unclear in part. While the Agreement refers to the CoE MLA system, to

which the UK made Declarations extending the scope of Application to other territories, including

Bailiwick of Jersey62 and Gibraltar63, the Agreement clearly states that it shall not apply to

Gibraltar.64

It was not possible to resolve this contradiction because an envisaged agreement between the UK and Spain concerning Gibraltar is not yet tabled.

Joint Investigation Teams

Art 62(2) of the Withdrawal Agreement allowed for UK authorities to continue to participate in Joint Investigation Teams (JITs) set up on the basis of EU law65 in which they were participating before the end of the transition period. However, the use of the Secure Information Exchange Network Application (SIENA) within the JIT was restricted to 1 year following the transition period.

The TCA66 now specifies that the relationship between Member States within the JIT shall still be

governed by Union Law, ‘notwithstanding the legal basis referred to in the Agreement on the setting up of the Joint Investigation Team.’ This means that the European legal framework on JITs67 will now apply between Member States even for those JITs that previously were set up on the basis of a non-EU law, such as, for example, Art 20 of the Second Additional Protocol to the 1959 CoE MLA Convention or the often forgotten Art 19 of the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (UNTOC), read in conjunction with its crime-specific protocols.68 In this context, ‘Member States’ must be understood as EU Member States, thus excluding the UK.69 This interpretation is also confirmed by Art 62(2) of the Withdrawal Agreement which also foresees that information sharing via SIENA (see above) will end by 2022.

However, most JITs are in fact set up under the CoE MLA system according to the Third JIT

Evaluation Report:70

‘Most JITs involving third States were set up on the basis of Article 20 of the Second Additional Protocol to the 1959 Council of Europe Convention. Article 19 of the UN Convention against Transnational Organized Crime was also used as a legal basis for setting up JITs’.

Therefore, the UK will be able to participate in JITs, but the communication channels are

restricted from those previously available, and this may impact upon the effectiveness of new and

existing JITs.

Preliminary analysis

The EIO was considered by many practitioners as a great achievement. It reconciled the prosecutor’s need to investigate with the suspects procedural and fundamental rights more specifically and clearly than any previous MLA instrument in Europe had done. The ordre public exemption was finally put into EU law, as well as the requirement of proportionality. And, another novelty, the right of the suspect or accused to also apply for an EIO was foreseen, and legal remedies had to be provided for.

Therefore, it is regrettable that the EIO no longer applies to the judicial cooperation with the UK.

At the same time, at least the proportionality threshold still applies, and is further stressed by the

exception of time limits for petty offences and the possibility to use an alternative investigative

measure that would achieve the same result by less intrusive means.

Moreover, the fact that MLA with the UK will now be generally treated as with third states makes

the time limits foreseen in the Agreement as highly ambitious, and probably, in most cases, unrealistic. MLA requests will take almost as long as with other third states, whereas within the EU, the EIO has considerably accelerated such requests.

Overall, the new provisions regulating MLA leave a lot of questions open. MLA can still

continue but at a much-reduced pace. The UK will be less flexible and responsive, and this will

hamper investigations in the UK and EU. Starting from the uncertainties about how the future

standard form will look like, only practice will answer the obvious question of how ‘old’ MLA

requests will be treated, hopefully in a more or less consistent manner. Further, it is yet to be seen how the competent authorities will deal with, in their view, disproportionate requests. Whether they are accepted by EU states and implemented quickly or whether the UK’s new status will put it to the back of the queue is yet to be determined.

Ben Keith is a leading specialist in Extradition and International Crime, as well as dealing with Immigration, Serious Fraud, and Public law. He has extensive experience of appellate proceedings before the Administrative and Divisional Courts, Criminal and Civil Court of Appeal as well as applications and appeals to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) and United Nations. He is ranked in Chambers and Partners as a band 1 leader in the field of Extradition at the London Bar and in the Legal 500 as a Tier 1 leading individual in international crime and extradition.

Click here for a full list of references.